Most people land here when they’ve set up a new tank (or changed a filter), tested the water, and seen ammonia or nitrite staring back at them. Those numbers matter because, in a closed glass box, waste doesn’t “disappear” — it changes form, and the timing of those changes can decide whether fish cope quietly or start to struggle.

Below is the aquarium nitrogen cycle in plain terms, what “cycled” actually looks like on a test kit, and how to steer a tank through the early weeks without crashing the biology that keeps the water safe.

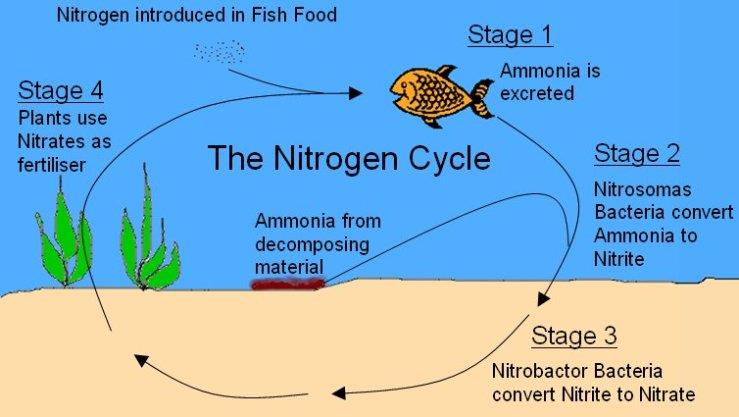

The nitrogen cycle (what’s happening in the water)

The nitrogen cycle is the slow, reliable work of microbes turning toxic fish waste into less harmful compounds. In most home aquariums, it runs in three main steps: ammonia becomes nitrite, then nitrite becomes nitrate. The bacteria doing this live on surfaces — especially in filter media — rather than floating freely in the water.1, 2

Stage 1: Ammonia (NH3/NH4+) appears

Ammonia comes from fish waste, leftover food, and any rotting organic matter. It’s the first spike in a new tank, and it can harm fish quickly. Toxicity depends strongly on pH and temperature because only the unionised form (NH3) is highly toxic; higher pH and warmer water increase the proportion of NH3.3

Stage 2: Nitrite (NO2–) rises

As ammonia-oxidising bacteria establish, ammonia drops and nitrite rises. Nitrite can interfere with oxygen transport in fish blood (often called “brown blood disease”), so a tank can look clear while still being dangerous.4, 5

Stage 3: Nitrate (NO3–) accumulates

Once nitrite-oxidising bacteria catch up, nitrite falls and nitrate becomes the main leftover. Nitrate is generally far less toxic than ammonia or nitrite, but it still needs managing with water changes and (if you have them) healthy, growing plants.2

What “cycled” means in practice

A tank is considered cycled when your test kit shows ammonia at 0 and nitrite at 0, with nitrate being produced (nitrate usually won’t be zero). At that point, your biological filter is functioning and can process the day-to-day waste load — as long as you don’t suddenly overload it with too many new fish at once.2

Establishing the nitrogen cycle in a new aquarium

Choose a cycling approach

- Fishless cycling (preferred): Add an ammonia source (commonly pure household ammonia or measured fish food) and let the bacteria colonies build before any fish go in.

- Fish-in cycling (higher risk): Cycling with fish present requires very frequent testing and water changes to keep ammonia and nitrite low. It’s easier to lose fish during this period, especially with heavy feeding or overstocking early.2

Where the “good bacteria” actually live

Most nitrifying bacteria colonise any oxygenated surface: filter sponges and bio-media, gravel, rocks, and plant leaves. The filter matters because it pulls water past those surfaces continuously, giving the bacteria first access to ammonia and nitrite.2

How long cycling takes

In a typical freshwater home aquarium, cycling often takes around 4–6 weeks, though it can take longer depending on temperature, pH, oxygenation, and whether the tank is seeded with established filter media. Expect it to be uneven — spikes don’t always follow a neat timetable.2, 6

Monitoring and testing (the quiet routine that prevents losses)

What to test, and how often

During the first six weeks of a new setup, test ammonia and nitrite every 2–3 days (more often if fish are already in the tank). Once the biofilter is mature and the tank is stable, testing every 1–2 weeks is usually enough for most community tanks.2

Liquid kits vs strips

Either can work if you use them consistently, but liquid kits are generally preferred for accuracy and clearer colour matching at low levels — the range where action matters most.

How to read results without overreacting

- Any ammonia or nitrite with fish in the tank: treat it as a prompt to act (reduce feeding, increase partial water changes, check filtration and aeration).

- Rising nitrate with zero ammonia/nitrite: normal for a cycled tank; manage with partial water changes and plants.

- High pH + warm water: increases ammonia risk because more TAN shifts into the toxic NH3 form.3

Managing the nitrogen cycle long-term

Keep the biofilter alive

Beneficial bacteria need oxygenated flow and stable surfaces to cling to. The quickest way to set a tank back is to over-clean filter media or rinse it under chlorinated tap water. If the filter needs cleaning, gently rinse media in a bucket of old tank water, then return it to the filter.2, 7

Water changes: small, regular, effective

Partial water changes dilute nitrate and other dissolved waste. A common baseline is 10–25% weekly (adjust up for heavy stocking, messy eaters, or rising nitrate). In the early weeks of a new tank — especially fish-in cycling — more frequent partial changes may be needed to keep ammonia and nitrite down.2

Common causes of sudden ammonia or nitrite spikes

- Adding too many fish at once (the bacteria population can’t expand overnight)

- Overfeeding or leaving food to rot in the substrate

- A power outage or blocked filter reducing oxygen and flow

- Replacing all filter media at once (removing the bacteria habitat)

- Using untreated tap water that contains chlorine/chloramine during water changes or filter cleaning2, 7

What imbalance looks like in fish and plants

Fish don’t need to “look sick” for the water to be unsafe. With elevated ammonia, you may see lethargy, reduced feeding, and abnormal swimming; prolonged exposure can damage gills and increase susceptibility to disease. Nitrite problems can show as rapid breathing and signs consistent with low oxygen stress, because nitrite affects oxygen transport in the blood.3, 4

Plants are more often affected indirectly: high nitrate can fuel algae, and unstable water quality can stall growth. Healthy plant mass helps by taking up nitrogen compounds, but it won’t replace filtration in a stocked aquarium.

Advanced options that make cycling steadier

Live plants (quiet nitrate consumers)

Fast-growing plants can take up nitrate and smooth out swings, especially in lightly stocked tanks. They also add extra surfaces for biofilms, which helps overall stability.

High-surface-area bio-media

Ceramic rings, sintered glass media, and sponge offer large surface area for bacteria. The goal isn’t a “stronger” cycle so much as a more resilient one: more habitat, more buffer against small mistakes.

Heavily stocked tanks need discipline

More fish means more nitrogen entering the system via feed, and more demand on oxygen and filtration. If you’re running a high bioload, rely on routine testing, consistent maintenance, and gradual stocking rather than “fixing” problems after the fact.3

Final thoughts

A healthy aquarium doesn’t stay healthy by luck. It stays healthy because waste is processed on schedule — ammonia first, then nitrite, then nitrate — and because the keeper protects the bacteria doing that work. Test calmly, change water when the numbers ask for it, and make changes slowly. Stability is what fish notice most.

References

- Encyclopaedia Britannica: Nitrification

- RSPCA Australia Knowledgebase: Why is water quality important when setting up a fish aquarium?

- NSW Department of Primary Industries: Monitoring ammonia

- Purdue University: Nitrite toxicosis in freshwater fish (brown blood disease)

- University of Florida IFAS Extension: Nitrite toxicity to fish

- Canberra & District Aquarium Society: Establishing a new aquarium

- Unusual Pet Vets (Australia): Basic water quality & nitrogen cycle for freshwater aquariums

- Government of Western Australia: Ammonia and fish (fisheries information sheet/PDF)

- United States EPA: Sources and solutions—nutrients (nitrogen in aquatic systems)

Veterinary Advisor, Veterinarian London Area, United Kingdom