Most people start looking up dog body language after a small moment of uncertainty: a wagging tail that doesn’t feel friendly, a dog that “looks guilty” but might actually be worried, or a sudden growl that seems to come from nowhere. Getting it wrong can mean a snapped lead, a frightened child, a fight at the dog park, or a dog pushed past its comfort zone.

Dogs speak in quiet, layered signals—tail height and stiffness, eye shape, mouth tension, weight shift—often long before they bark or bite. The aim is to read the whole animal in context, then choose the safest next step: give space, slow things down, or call it and walk away.1, 2

How to read a dog: start with the whole body

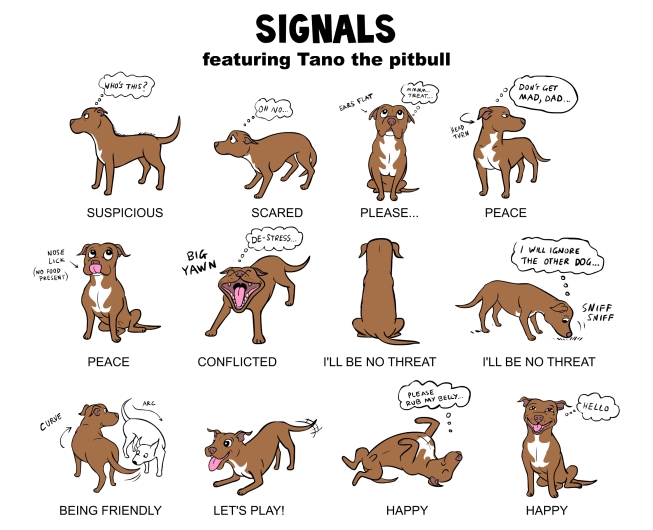

A single signal can mislead. A wagging tail can sit on top of tension. A yawn can be fatigue—or a stress release. The most reliable approach is to scan from nose to tail and ask: does this dog look loose and flowing, or tight and held?

- Loose body: curved spine, soft face, easy breathing, movements that look unhurried.

- Tight body: stiff legs, weight pitched forward or pulled back, mouth shut tight, eyes wide or hard, movements that look sharp or frozen.

Context matters. A dog on lead, behind a fence, guarding a doorway, or approached face-on is more likely to feel pressure than the same dog in open space with room to move away.2

Tail language: wagging is arousal, not a guarantee of friendliness

The tail is an arousal meter, not a friendship flag. A dog can wag because it’s excited to greet, but it can also wag when it’s unsure, overstimulated, or preparing to escalate. Read the tail with the rest of the dog.1

- Neutral, loose wag (tail held at the dog’s normal resting height): often relaxed engagement.

- High, stiff tail (sometimes with a tiny vibration): assertive arousal; give space.

- Low tail or tucked tail: fear, stress, appeasement, or discomfort.

- Fast wag at the tip with a tight body: a warning sign in some dogs—don’t assume it’s playful.

“Neutral” tail carriage varies by breed and individual (a curled tail, a naturally low tail, a docked tail). Learn your dog’s baseline when it’s calm at home, then notice departures from that norm.1

Ears, eyes and face: small changes with big meaning

Dogs broadcast emotion through tiny shifts: ears angle back, the skin around the mouth tightens, the eyes go from soft to round. In many breeds, these changes happen seconds before a lunge or snap—long before a bite.

Ears

- Forward/pricked: alert, aroused, focused (not automatically “happy”).

- Pinned back tightly: fear or high discomfort.

- Back but loose: can be calm appeasement, depending on the rest of the body.

Ear shape matters. With floppy-eared breeds you’ll see more movement at the ear base and on the forehead than at the tips.1

Eyes

- Soft eyes, normal blink rate: calmer state.

- Hard stare: pressure, challenge, guarding, or high arousal.

- “Whale eye” (white of the eye showing at the corners): fear, anxiety, or discomfort—especially if the head is turned away but the eyes stay locked on the trigger.

- Averted gaze/head turn: an appeasement signal; often a request for space.

Brief eye contact can be fine. A sustained stare, especially from a stranger, can feel threatening to a dog that’s already unsure.1, 2

Mouth and facial tension

- Relaxed, open mouth (in cool conditions, without frantic panting): often calmer.

- Tight, closed mouth: uncertainty or rising stress.

- Lip licking, yawning (when it’s not about food or sleep): common stress and conflict signals.

- Teeth showing, lip lift, growl: distance-increasing warnings—don’t punish them; create space.

These “fiddle behaviours” (yawn, lick, blink, head turn) often appear early. If you respond then—by pausing, stepping back, or reducing pressure—you may never see the louder signals.1

Posture and movement: the weight shift tells the story

Think of posture as the dog’s headline.

- Weight forward, body tall and stiff: assertive arousal; higher risk if combined with a hard stare and high tail.

- Weight back, crouched, low head: fear or uncertainty; higher risk if the dog can’t escape.

- Frozen stillness: a serious moment. Many dogs go quiet and still right before escalation.

- Curved approaches (not walking straight in): polite social behaviour; many dogs prefer angles over direct, face-on greetings.

- Play bow: often an invitation to play, but it can also appear as a stress release in tense moments—again, read the whole dog.

A dog that can move away usually will. A dog that can’t—cornered, held on a short lead, crowded by people—may choose growling or snapping instead.1, 2

Stress and discomfort: common early warning signs

These signals are easy to miss because they look ordinary. Out of context, they’re often the first visible cracks in the dog’s comfort.

- Yawning when not tired

- Lip licking when not eating

- Frequent blinking

- Turning head away or avoiding eye contact

- “Whale eye”

- Panting when not hot or exercising

- Full-body shake when not wet

- Tail tucked or carried low

If several appear together, treat it as a request for space and a sign to lower the intensity of the interaction (less reaching, less talking, more distance).1, 3

Signs of fear, conflict and aggression: what to do in the moment

A dog’s behaviour often escalates because earlier signals were missed. When you notice a shift towards tension, aim for safety and distance rather than “testing” the dog.

When a dog looks fearful

- What you may see: crouching, tail tucked, ears pinned back, lip licking/yawning, looking away, trying to move away.

- What helps: stop approaching, turn your body sideways, give an exit route, keep hands low and still, and reduce noise and crowding.

Fearful dogs can bite if they feel trapped. Creating space is not “rewarding fear”; it’s removing pressure.2, 4

When a dog looks conflicted (mixed signals)

- What you may see: tail wagging with a stiff body, moving forward then backing off, barking while retreating, yawning while staring.

- What helps: treat the situation as higher risk. Pause, increase distance, and avoid direct contact.

Conflicted dogs are unpredictable because they are still deciding what to do next.4

When a dog looks assertive or aggressive

- What you may see: tall stiff posture, weight forward, hard stare, high stiff tail (may still wag), raised hackles, lip lift, growl, lunge.

- What helps: do not reach in, do not stare, do not run. Create distance calmly and put a barrier between you and the dog if you can.

Growling and snarling are warnings. Heed them. If a dog is regularly reaching this point, seek help from a vet (to rule out pain) and a qualified trainer or veterinary behaviourist.2, 4

Vocalisations: useful, but secondary

Barks, whines and growls add colour, but they’re rarely the whole message. Some dogs are noisy and relaxed; others are silent and tense. Use sound as a supporting detail.

- Growling: a clear “increase distance” signal, whether the dog is guarding, frightened, or overstimulated.

- Whining: can appear with frustration, uncertainty, or anticipation—look for tense posture or pacing to interpret it.

- Barking: can be alarm, excitement, play, or distress; match it to body stiffness, tail carriage and eye shape.

If the body is tight, treat the situation as serious no matter how “friendly” the sound seems.4

Training and day-to-day handling: use your own body language

Dogs watch us closely. Small changes in our posture and speed can turn a manageable situation into a stressful one.

- Approach in an arc rather than straight on, especially with unfamiliar dogs.

- Turn side-on and soften your gaze instead of leaning over a dog.

- Reward calm choices (looking away, sniffing, checking in) and give breaks before your dog is overwhelmed.

- Avoid punishment for warning signals like growling; it can suppress the warning while leaving the discomfort intact.

Where possible, use structured socialisation and positive reinforcement training so the dog learns that novelty and handling predict safety, not pressure.2, 5

Health and wellbeing: when body language suggests pain or illness

Not all “bad behaviour” is behavioural. Pain can change how a dog moves, tolerates touch, or copes with routine handling. Watch for a sudden shift from a dog’s normal baseline.

- Reluctance to jump, climb stairs, or sit/lie in a usual position

- Stiffness, limping, guarding a body part

- Withdrawal, irritability, reduced tolerance of touch

- Persistent panting, restlessness, unusual stillness

If you suspect pain, book a veterinary check rather than trying to “train through” it. Modern veterinary guidelines emphasise recognising pain early and treating it properly, because unmanaged pain affects welfare and behaviour.6

Quick safety check: before you pat any dog

- Look for a loose body and soft face.

- Avoid dogs showing whale eye, lip licking, yawning, stiff posture, or hard stare.

- Ask the owner first. If you get a yes, let the dog come to you. Keep your hands low and pat the chest/shoulder area rather than reaching over the head.

- If the dog freezes, leans away, or the mouth closes tight—stop and give space.

These small habits reduce bite risk and give dogs more choice in how they interact with us.4

References

- RSPCA Pet Insurance (Australia): How to interpret body language in dogs

- RSPCA Knowledgebase (Australia): How do I communicate with my dog?

- RSPCA Knowledgebase (Australia): What does my dog’s body language mean?

- ASPCA: Dog Bite Prevention

- ABC News (Australia): Dog bite campaign aims to reduce attacks, better educate about canine behaviour and warning signs

- WSAVA: Global Guidelines for the Recognition, Assessment and Treatment of Pain

Veterinary Advisor, Veterinarian London Area, United Kingdom